We are very grateful to Kristine Pedersen from Kommunikationscentret in Denmark for sharing the findings of 2 projects with us. The first project found Talking Mats was effective in supporting communication for people who have dementia when compared with both unstructured and structured conversations.

‘t is important to know how to give people with dementia the right support’

At Kommunikationscentret in Hillerød (Denmark), we have been using the Talking Mats framework since our first trainer was accredited at the Talking Mats Centre, University of Stirling in 2010. We have been using Talking Mats with both children and adults across a range of communication difficulties e.g. caused by Aphasia, Cerebral Palsy, Downs Syndrome, learning difficulties etc. Inspired by the important research project by Dr. Joan Murphy and others ‘Decision making with people with dementia’ (2010), our next step was to gain our own experience within the framework specifically aimed towards people with dementia.

As in the rest of the world, the number of people in Denmark with dementia is increasing. Symptoms of dementia vary from person to person but many of the symptoms are related to communication: Difficulties finding words, using familiar words repeatedly, losing track in conversation, difficulties in focusing and paying attention etc. The growing dependence of the person with dementia on a caregiver makes communication essential to express wishes and needs. Therefore, it makes sense to look at the consequences of the illness (dementia) within the perspective of communication and how family members and professionals around the person with dementia can support communication using AAC.

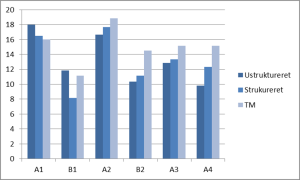

The purpose of the first project was to compare the communication in conversations about views on I) Daily activities and II) The importance of information, using three different communication methods. The methods were: 1) unstructured conversation 2) structured conversation 3) the Talking Mats framework. The project involved 6 participants having early to moderate stage dementia, all living in residential care homes.

Like the study ‘Decision making with people with dementia’ (2010), the report concludes that the Talking Mats method was associated with better communication for the majority of the participants. The Talking Mats framework was found especially helpful regarding the participant’s ability to understand subject and question of the conversation, the participant’s ability to reflect, and the participant’s ability to make themselves understood. The graph below shows that only one participant (A1) did not benefit from the visual method. She had poor eyesight, which strongly indicates that visual support compensates the difficulties that people with dementia have.

The report also concludes that the Talking Mats framework increases the interviewer’s ability to detect and compensate for some of the communication difficulties. Finally, it seemed that several of the participants have been able to learn how to use Talking Mats in the process.

The photo underneath shows a Talking Mat conversation from the project. This Talking Mat gives an insight into how this person feels about what information is important to her, and what isn’t. It is in some way a difficult and abstract question, but most of the participants managed to both understand, reflect and answer the question when we used the Talking Mats framework.

Important information to this participant is information about new neighbours, the menu at the residential care home, economy etc. Less important is news about the Danish royal family, technology, getting older etc. Politics is definitely not important to her.

We are very grateful to Tom Tutton from Autism Spectrum Australia for this interesting blog.

Autism Spectrum Australia (Aspect) works with people on the autism spectrum and their families. We regularly recommend visual communication strategies because people on the spectrum often have strengths in visual learning. This is especially important in our work through Aspect Positive Behaviour Support where communication can replace challenging behaviour.

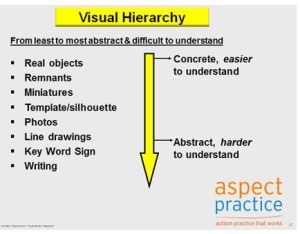

In the past, we applied a ‘hierarchy’ of visual representations based on how easily they can be understood.

Generally, objects are considered the easiest form of visual communication to understand; followed by miniatures, remnants, photos, line drawings and symbols and writing, in that order. Although this hierarchical understanding is held true for many people on the spectrum, there can be exceptions. Some individuals find line drawings easier to understand than photographs.

Aspect Practice continually reviews and applies the evidence base to our daily work. So, with the knowledge that the hierarchy does not fit for some people, we reviewed the research literature to see if we could refine our understanding and use of visual communication strategies.

We asked “What evidence is available about the hierarchy of visual representation which could explain how an individual could benefit more from line drawing supports than photos?”

To find the answer, we searched an electronic research database, prioritised 20 papers and then reviewed four papers in detail that seemed to answer our question (references below).

We found information that suggests the factors contributing to a person’s understanding of visual symbols is broader than a simple hierarchy and involves consideration of three main areas:

The individual’s experience

- The individual’s ability to learn

- ‘Iconicity’ of the symbol (more detail about this piece of terminology below)

Ideally, these factors should be considered for every symbol used with every individual. We learned that a symbol can be placed on a continuum in terms of ‘iconicity’. At one end, it can be described as “iconic” or “transparent”, meaning that it is very similar to the object it refers to (e.g. using a juice bottle to present the choice of juice). At the other end, it can be described as “arbitrary” or “opaque”, meaning that there is little or no visual similarity between the real item and the symbol (e.g. the written word “bird” does not look or sound anything like an actual bird).

The generally accepted hierarchy of visual representations aims to organise types of symbols by their level of iconicity, but misses some subtleties. This means that phrases such as “photos are easier to understand than line drawings” are often overgeneralisations.

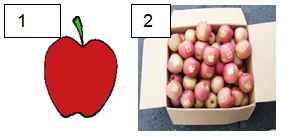

For example, image 1 looks more like an apple than image 2, even though the second one a photograph. Image 1 would also be easier for an individual to understand if that symbol had been used extensively around them, if it was motivating and functional and if that individual had a strong ability to learn the association of that symbol and an actual apple. Therefore, a person’s ability to understand a symbol does not depend on its iconicity alone, but the ways symbols are used and learned.

In answer to our question, there are several possible explanations why a person may understand line drawings better than photos.

They may have been exposed to line drawings more than photos, meaning they can learn the associations between line drawings and things in the real world more effectively.

- The photos being used contained a background (and had lower ‘iconicity’), whereas the line drawings provided a simple representation on a plain white background.

- The person’s learning style may mean they learn each symbol individually, rather than learning how to associate symbols the real objects in a more general way. If a person who learns this way is exposed to more line drawings, they will learn more through line drawings.

As a general statement, it is clear that greater emphasis needs to be placed on the needs of the individual, as well as the properties of the individual symbol, rather than considering only a hierarchy.

Steve Davies (Positive Behaviour Support Specialist & Speech Pathologist, Aspect Therapy)

Dr Tom Tutton (National Manager, Aspect Practice, Positive Behaviour Support Specialist)

References

- Fuller, Lloyd & Schlosser (1992) Further Development of an Augmentative and Alternative Communication Symbol Taxonomy, AAC Augmentative and Alternative Communication, pp67-74

- Sevik & Romski (1986) Representational Matching Skills of Persons with Severe Mental Retardation, AAC Augmentative and Alternative Communication, pp160-164

- Stephenson & Linfoot (1996) Pictures as Communication Symbols for Students with Severe Intellectual Disability, AAC Augmentative and Alternative Communication, pp244-256

- Dixon, L. S., (1981) A functional analysis of photo-object matching skills of severely retarded adolescents, Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis, 14, pp465-478

This article was inspired by a blog post written by Dr Joan Murphy, Co-Director, Talking Mats.

Click here to read original blog

Aspect Practice is an initiative where Aspect shares its evidence based practice through information, workshops and consultancies. To learn more about Aspect Practice, visit www.autismspectrum.org.au/content/aspect-practice.

I’ve been thinking about the advantages and risks of social media after Talking Mats recently reached 10K Twitter followers.

We (and by we I really mean my co-director, Lois, who had the vision – and at times the addiction! -to embrace and develop social media for Talking Mats) have worked hard at engaging with people who have a similar ethos as us i.e. to support and improve the lives of people with communication disabilities. We have linked with people who could teach us new ways of looking at the world we work in and with whom we could share our ideas. We realised that social media is a powerful tool to connect with like-minded people across the world. In combination with Twitter and Facebook we write regular blogs illustrating relevant- and at times fun – issues from our work. We hope our website is seen as a rich resource of information for anyone interested in communication.

However, I recently listened to a TED talk given by Wael Ghonim. He spoke about how in 2011 his use of social media helped spark the Arab Spring when he set up a Facebook page which attracted tens of thousands of followers and became a place for crowdsourcing and sharing. However, his initial euphoria turned to despair as the revolution turned ugly and the social media he was involved with also turned unpleasant. He describes what he now believes are 5 main problems with the direction that social media has taken.

- Social media can spread rumours that become seen as truth

- Social media can result in ‘echo-chambers’ – we only communicate with people we agree with

- Social media can quickly shift from discussion to disagreement and anger

- Social media encourages us to make statements (as a result of having only 140 characters) rather than ask questions about complex issues. Everyone can read these statements and we feel we need to defend them

- Broadcasting becomes more important than engagement; shallow comments become more important than discussion; we talk AT people rather than WITH each other; we become obsessed with numbers of posts and followers rather than with the quality of the discussion and who follows us.

He concluded his talk by suggesting that we need to develop social media protocols to create civility and respect and reasoned argument e.g. get credit for the number of people whose mind you change. I found his arguments compelling and uncomfortable – I do recognise Wael Ghonim’s ‘problems’ when I venture into other areas on social media such as politics.

However, this has not been our experience and we are reassured that in the social media world of communication disability people are civil, respectful and generous. We at Talking Mats like to think that we are using social media as a forum for engagement, thoughtfulness, quality discussions, learning new ideas and developing understanding without hostility, anger and shallowness..

And long may this continue…..

One of the issues which has emerged from previous Talking Mats and dementia projects is that many people with dementia experience difficulties with mealtimes and that it can affect people at any stage of dementia.

Mealtimes involve two of our most fundamental human needs, the basic physiological requirements for food and drink and interpersonal involvement. Mealtimes are particularly important for people with dementia as they may develop difficulties both with eating as a source of nourishment and with the social aspects of mealtimes.

In 2015 Joan Murphy and James McKillop carried out a project, funded by the Miss EC Hendry Charitable Trust, to gather information from the first-hand experience of people with dementia about their views about mealtimes. We ran three focus groups and used the Talking Mats Eating and Drinking Resource to allow participants to reflect, express and share their views.

Findings:

The people who took part in this study felt that there were significant changes in their eating and drinking since their diagnosis of dementia. For some, their experience of mealtimes had changed and several said that they now skip breakfast and sometimes lunch. For some this seemed to be related to forgetting to eat and drink, for others it related to changes in taste whereas for others these meals seemed to be simply less important. Forgetting to eat was particularly noted by the participants with dementia and confirmed by their spouses.

The social aspect of eating and drinking also changed for many of the participants and, given the importance of social engagement for quality of life it is important to be aware of the effects of changes in eating and drinking on mealtime dynamics. For some it may be that they are now less interested in the social aspect of eating with others at home. Others found it hard to eat out because of distractions and lack of familiarity while some felt embarrassed about eating out in front of strangers. Others still really enjoyed going out for meals but added that they preferred to go somewhere well-known to them. The shared mealtime may be a particularly crucial opportunity for social engagement as it plays a central role in our daily lives. Social relationships are central for not only enhancing quality of life, but also for preventing ill health and decreasing mortality (Maher, 2013).

Almost all the participants talked about how their taste had changed both for food and drink which in turn affected their appetite. Some families had overcome the problem of lack of taste by going for more strongly flavoured food. When asked specifically about drinking, thirst was noted as a significant change since diagnosis

Their feelings about the texture of food did not appear to have changed significantly and was simply a matter of preference.

Three additional health issues which the participants felt were connected with eating and drinking were poorer energy levels than before their diagnosis, reduction in ability to concentrate and changes in sleep patterns.

For a copy of the full report please click here Dementia and Mealtimes – final report 2015

Online training login

Online training login