We are delighted to share a poster from Licenced Trainers Brid Corrigan and Libby Mills of NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde, and Student Speech and Language Therapist Heather Pollock, developed as part of an Impact Project with the University of Strathclyde.

The poster reports on an evaluation of the impact of Talking Mats training on clinical practice across several Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in and around Glasgow. We were thrilled to hear the poster had been accepted at the Solving the Mental Health Crisis: Global Solutions Across the Lifespan Conference, held on Friday 21st June.

The project demonstrates how Talking Mats can be used by several members of the multidisciplinary team to build rapport and set goals with young people in both the inpatient and community CAMHS setting. A huge well done to everyone involved in the project for shining a light on how Talking Mats can help to hear the young person’s voice as part of their CAMHS journey.

We are pleased to share a new blog from Talking Mat Associate, Jess Lane, as part of a 2-part series on the use of Talking Mats within Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

In Part 1, Jess described how Talking Mats can provide children with a safe space to explore topics that they might otherwise feel unable to communicate about, in a way that is highly supportive, sensitive and impactful. Check it out here:

In Part 2, Jess reflects on the use of Talking Mats by all members of the multidisciplinary team. We also hear from Nikki Low, Specialist Occupational Therapist, who reflects on her use of Talking Mats in the acute mental health setting.

Later in the blog, Jess explores how Talking Mats can be used as part of a post-diagnostic package of support for autistic children to support more focussed, strengths-based conversations, in line with the core principles of neurodiversity affirming practice.

A Multidisciplinary Approach

Welcome back to my 2-part series on the use of Talking Mats within CAMHS. In Part 1, I described how the implementation of Talking Mats by all members of the multidisciplinary team has transformed the way children are supported in the acute mental health setting. I have since reflected with clinicians from across Speech and Language Therapy, Nursing, Psychiatry, Dietetics, Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy and Psychology on how Talking Mats continue to be used on CIPU to facilitate the direct and meaningful involvement of children in care planning, and to facilitate equity of access to therapeutic intervention.

Nikki Low reflects on using Talking Mats in her role as a Specialist Occupational Therapist:

“I am a Specialist Occupational Therapist working in a Psychiatric Inpatient Unit with children under 12, many of whom, in addition to their mental illness, have an intellectual disability, are neurodivergent and/or have experienced complex trauma. This can make meaningful interactions about thoughts and feelings challenging or even impossible, particularly when discussing sensitive topics.

We strive to provide a client centred approach to care and treatment for our young patients but this can be difficult when they are unable to express themselves. Talking Mats has revolutionised our approach with these children. It has proven to be a powerful tool, transforming communication experiences for individuals of all abilities. I have used Talking Mats to engage patients in assessments and to formulate their treatment goals. Its user-friendly design, customisable features and positive impact make it an invaluable resource in the care and treatment of our vulnerable young patients.

As a unit, we have rolled out training to all core staff in order that we can incorporate Talking Mats into our practice. By doing this, we have been able to facilitate more inclusive and person-centred interactions, ultimately fostering a more supportive and empowering environment for all involved.”

Implementing Talking Mats across a whole staff team has increased the capacity and capability of clinicians to routinely involve children in decisions pertaining to their care. It has also contributed to a culture whereby Talking Mats are considered at each stage of a child’s admission, to support assessments of capacity and mental state, medication reviews, engagement with advocacy services and participation in all multidisciplinary team meetings and case conferences.

Post-Diagnostic Support

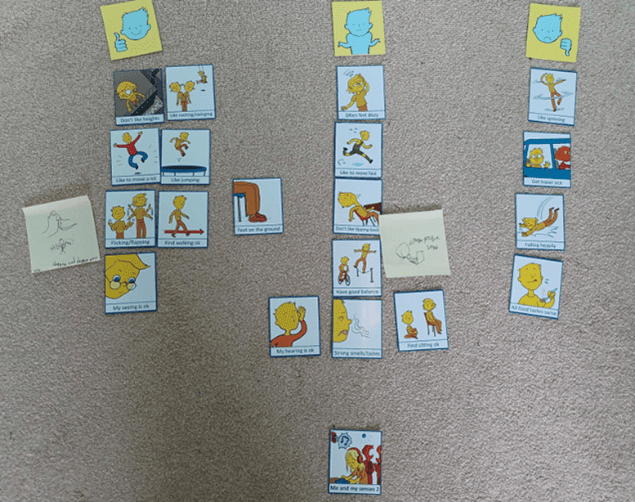

Most recently, I have used Talking Mats as part of a post-diagnostic package of support for autistic children, to support more focussed, strengths-based conversations around what it means to be autistic. This has involved developing a symbol set based on SIGN guidelines and associated resources, to support children who have recently been diagnosed as autistic, to engage in a conversation about what would be helpful for them to know.

When presented with a Top Scale of Helpful, Not Sure, Not Helpful, children were able to share their opinion on a range of options, including (but not limited to): facts and figures, autistic famous people, links to other work, skills, strategies and resources. An example is provided below. From this, I was able to create a personalised information pack for each child, based on what they would (and would not) find helpful to know about autism.

Most children shared that it would be helpful to find out about autistic famous people. This provided the foundation for a follow-up conversation about identity. Some children shared that they would find it helpful to find out about incidence and prevalence figures. Others did not. This was reflected in their information packs. For children who shared that they would like to understand how being autistic might impact, or otherwise feed into, therapeutic work for anxiety, I worked with colleagues from across Psychology and Nursing to ensure this was accurately reflected in their information packs.

Using a Talking Mat to scaffold conversations about what it means to be autistic has been well received by other clinicians involved in providing post-diagnostic support. By providing children with an opportunity to identify exactly what they would like to know about autism, clinicians have been able prioritise areas of support and signpost to the most relevant resources. This speaks to legislation that calls for the greater involvement of patients in decision making, in line with the mantra: no decision about me, without me.

Anecdotally, I have found that using Talking Mats as part of a post-diagnostic package of support has made a significant contribution to the development of a more streamlined, relevant and person-centred approach to sharing information. Using Talking Mats in this way has provided children with a dedicated space to voice their opinion on a topic that they might not have previously inputted into, that has been actively listened to and directly acted upon.

It is hoped that in sharing how Talking Mats can be used as part of a post-diagnostic package of support, this blog might encourage others to consider how they might achieve similarly positive outcomes for children with other diagnoses. If you have used Talking Mats as part of a post-diagnostic package of support for children or adults, I would love to hear from you! Please do get in touch at info@talkingmats.com.

Our thanks for this blog go to Deborah Little, Speech and Language Therapist; Clinical Lead for AAC & Total Communication (Children and Young People) NHS Dumfries and Galloway.

“Can we do a Talking Mat today Deborah? This is the question I am asked as soon as I enter the Learning Centre in one of our local schools by an enthusiastic 8 year old who has been exploring what completing a Talking Mat (TM) is all about this term. While we are in the early stage of this school’s TMs journey, the impact of embedding the approach into the fabric of how Children and Young People (CYP) are supported to communicate in school is already proving transformative.

Article 12 of The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) guarantees children the right to express their views and opinions freely in all matters affecting them. The responsibility of ensuring children experience this right is also underlined in NICE guidelines (2022) that state: “Education, health and social care practitioners should always: put the life goals and ambitions and preferences of the disabled child or young person with severe complex needs at the centre of planning and decision making.”

Working with my teaching colleagues within one Additional Support Needs (ASN) setting this year, we reflected on how effectively the CYP were able to give their views and how consistently these views were acted upon in meaningful ways. We felt that this was an area we really wanted to improve upon and specifically we wanted to explore the following key questions in our minds:

- How can we support CYP’s understanding of their right to give their views and opinions? We reflected that for some CYP, their experience of being able to do this was very limited and that their understanding of using a TM was not yet at a stage where they were able to represent their views. We therefore wanted to prioritise finding out what helped these CYP to use TMs with understanding.

- How can we support CYP to know that they can tell us they aren’t happy about something? We reflected that during ‘Emotions Works’ discussion times many of the CYP routinely shared that they felt ‘happy.’ It was rare for the CYP to talk about unhappy feelings. We felt worried that the CYP often gave responses that they felt would be ‘right’ or pleasing to adults.

- How can we ensure we create a culture of prioritising time and space for CYP to share their views, opinions and ideas? We thought about opportunities throughout the school week that would create space and motivation for the CYP to engage with TMs. We wanted to achieve a feeling of TMs being integral to the everyday, as opposed to a sporadic ‘add on.’

To answer these questions, we agreed on the following key change ideas to implement and evaluate:

Developing understanding of the Talking Mats process linked with familiar learning opportunities.

Dynamic Assessment is an approach familiar to those working with CYP who use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). Adapting activities dynamically, being responsive to CYP’s progress, allows progressive skill enablement. Together with teaching colleagues, we applied this thinking to helping the children use TMs with understanding. If we had tried having a conversation using TM only a couple of times, our evaluation could have been that TMs wasn’t yet a tool we could use because for example, the CYP were putting all their symbols into the ‘I’m happy with this’ column only. Instead, we thought “OK, that’s where the CYP are now, let’s give them opportunities to practise engaging with this new tool and time to develop using the approach with understanding.” Put another way, we prioritised another key concept within the field of AAC: we Presumed Competence. We believed that the CYP had the ability to share their thoughts, feelings and ideas if we introduced TMs gradually, linking with the activities above, that were tangible and familiar to the thinkers.

Consciously modelling that is OK to have negative feelings and opinions.

When a CYP is learning what might be possible in terms of communicating with AAC, best practise is for supporting adults to model the AAC. This means, adults ‘use AAC to teach AAC.’ We show CYP that we highly value the AAC and want to use it too. We use it in real situations, modelling vocabulary to help CYP understand the symbolic vocabulary and how they can begin to use it too. When helping the CYP understand how TMs could help them express a wider range of emotions, we tried out using this approach. Now and again, supporting adults would share with the CYP how they were feeling about things using TMs and would include negative feelings.

One CYP had a memorable response to my sharing that I was feeling “not happy” with my cat. The CYP’s eyes widened and he became instantly animated, using his AAC to ask “cat..bad..what?” I was able to explain that my cat had been scratching my carpets and I was feeling upset about this. The CYP then used his AAC to say “cat…dig!” He pointed at the ‘not happy’ symbol in the Talking Mats top scale, jointly sharing his attention to this symbol and understanding of what this meant with me. The next week, we used TMs to ask this young person about a social group he had attended. For the first time, we noticed him ‘swithering’ across his top scale while making his choices. Also for the first time, I was confident that he shared his authentic feelings with me. I reflected on the power of modelling and normalising feelings that are ‘not happy.’

So, where are we now? The key themes from our findings after a year of using TMs as described above are:

In summary, using TMs in this setting has all supporting practitioners in agreement that it is not only important to listen to CYP when we know they might be having a tough time; we need to create space to listen all of the time, week to week, with authenticity and without agenda. The principles regularly used within AAC practice of: modelling, presuming competence and dynamic assessment have been effective in supporting more children to be able to experience their UNCRC Article 12 Right, more of the time and with increased understanding and confidence.

References

- UN Convention on the Rights of the Child – UNICEF UK

- NICE Guidelines [NG213] (2022) Disabled Children and Young People up to age 25 with severe complex needs: integrated service delivery and organisation across health, social care and education.

- Emotion Works www.emotionsworks.org.uk

- Daneshfar, S and Moharami, M (2018) Dynamic Assessment in Vygotsky’s Socioculturaly Theory: Origins and Main Concepts. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 9(3):600

- Donnellan, A (1984) The Criterion of the Least Dangerous Assumption. Behavioural Disorders, 9 (2), 141-150

- Sennott, Light and McNaughton (2016) AAC Modelling Intervention Research Review. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilties 41 (2)

Our thanks for this guest blog go to Meredith Smith, Paediatric Physiotherapist and Lecturer in Physiotherapy in the School of Allied Health Science and Practice at the University of Adelaide. In this blog, Meredith talks about the development of a Talking Mats resource to facilitate self-reporting in pain assessments for children and young people with cerebral palsy.

Our research team has been working on modifying pain assessment tools so they are more appropriate, relevant and accessible to children and young people with cerebral palsy (CP). People with CP have varying functional, communication and cognitive abilities, which makes existing assessment tools (often pen and paper questionnaires) difficult to use across the spectrum of ability. As a result, children and young people with CP often don’t have the opportunity to self-report how pain is impacting their function.

We are based in Australia and our team is made up of physiotherapists, an occupational therapist, a medical practitioner, researchers and people with lived experience of CP. One of the first things we did as part of this project was to ask people with lived experience of CP and clinicians what we could do to make two specific pain assessment tools more accessible and relevant to people with CP and different abilities. One of the clinicians (a speech pathologist), suggested we consider a Talking Mat alternative for each of the assessment tools. These two assessments focused on two concepts – 1) how pain interferes with function and 2) pain-related fear. We were keen to focus on these assessments as this would help us to not only open up a conversation about pain with children and young people with CP, but would also provide us with a way of identifying children who might benefit from particular pain interventions, and allow us to monitor the effectiveness of these interventions.

Prior to this suggestion I had heard of Talking Mats but never used it. Our research team underwent Talking Mats foundation training which was excellent, and we were all really impressed with the concept and its application in varying contexts. We had initially thought that we might need a Talking Mat to get feedback from children on the assessment tools, but we all agreed that converting the pain assessment itself into a Talking Mat would make the most sense for now.

Working with the Talking Mats team was a fantastic experience. We all really appreciated the expertise of the consultants in considering how we worded some of the assessment tool items. The symbols created were also excellent, and when we tested them with children and young people with CP they were simple and easy to understand.

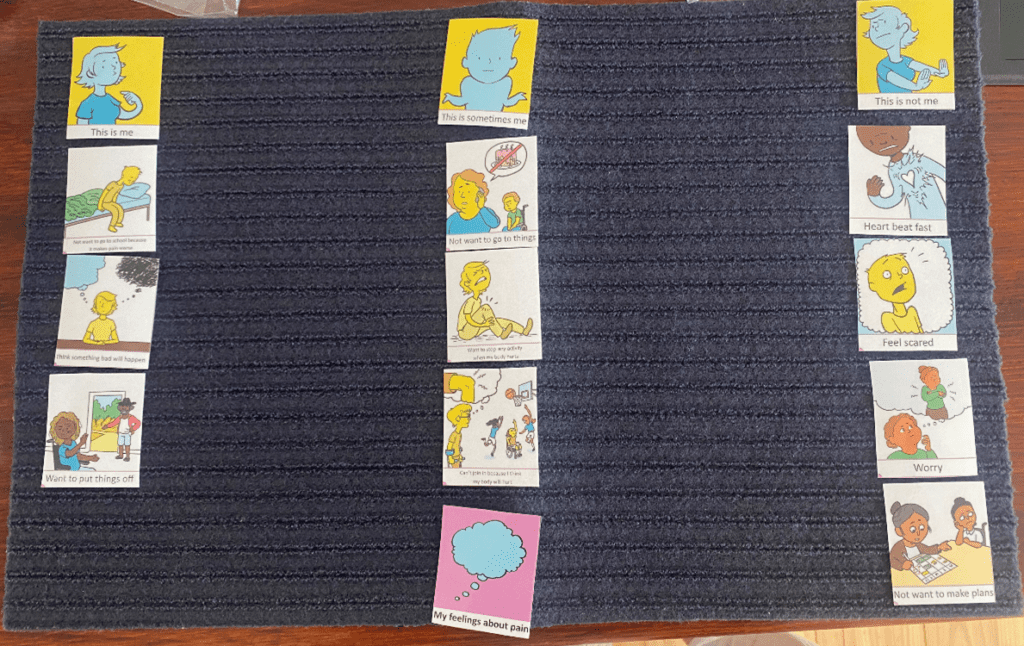

Here is an example of a Talking Mat discussing pain interference with function. The lead in phrase is ‘how much does pain get in the way of……’. This Talking Mat was easily understood by most children with CP, even those with moderate cognitive impairment and complex communication needs.

The second Talking Mat looked at pain related fear, with the lead in phrase ‘pain makes me……’. This was a more challenging and abstract concept, but was much easier to explore using the mat than on a standard pen and paper questionnaire. The Talking Mat versions can be interpreted as a 5-point response scale (the three response options and then two in-between sections), allowing us to still total an overall score for the assessment.

The feedback from children, young people and their families has been very positive. Families of children with cognitive impairment or complex communication needs have shared with us that previously it was assumed that their child could not self-report pain, and often they were asked to proxy-report on their behalf. Parents have told us how difficult it is to proxy-report on personal concepts such as pain-related fear, and that they couldn’t possibly know for certain how pain was making their child feel.

We are in the process of continuing to test the Talking Mats resource and look forward to making the it more widely available in the future.

Keep an eye on our website for more information about the Pain Assessment Resource as this project progresses.

If you are interested in completing Talking Mats Foundation Training, you can find out more here.

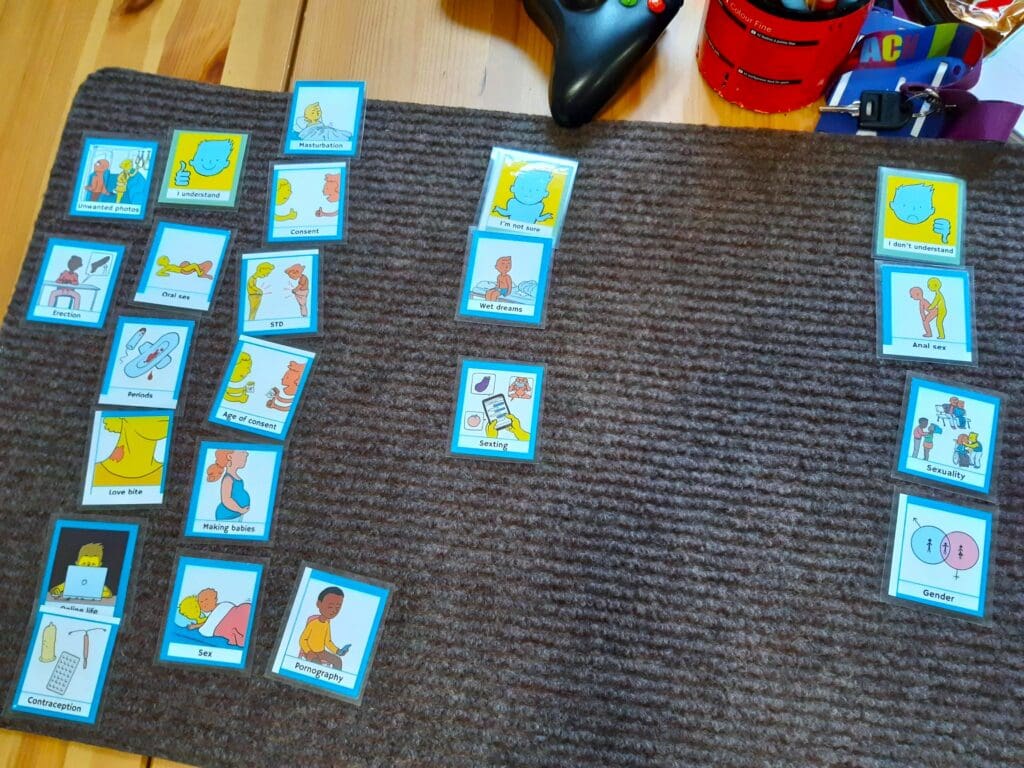

Thanks to Julia Pollock, Highly Specialist Speech and Language Therapist (SLT) from the REACH team in Perth for the second part of this latest guest blog sharing information about our exciting project, which has aimed to produce a resource to open up conversations with young people about sex.

By far, the most impactful feedback we’ve had during the pilot stage of this project has come from the social worker of the young person who I initially created the resource for. She was very keen to share with us that she had used the resource with the young person (two years on) and said it was ‘absolutely fantastic – I can’t tell you how good it was’.

Using the updated version, she was able to revisit the young person’s sexual knowledge and understanding and found that he was able to understand and have adult discussions around much more complex and abstract concepts than he had previously. The concepts included consent, contraception and sexually transmitted diseases. This was in stark contrast to his initial bewilderment when we first introduced the resource to him!

This has been a perfect case study for us as the resource has been used to support this young person through their entire criminal justice journey and through their sexual development into adulthood. The first draft had been used to initially gather information about his sexual knowledge and understanding in addition to information about the harmful sexual behaviour. It was later used to guide and support his sex education.

Now we have come full circle, with social work using the updated version of the resource to reflect on the past, helping him to understand his sexual development and to help guide his understanding around navigating future adult relationships in a safe and appropriate way.

‘He is ‘a confident, happy young man with the knowledge he needs for the future. There has been a lot of repair to his sense of self and moving from describing himself as a “monster” to understanding that he had a lack of knowledge and didn’t have the skills to navigate his sexual development safely. He is now able to accept his sexual feelings as being a “normal” part of development and to think how these can be expressed safely. His ability to integrate knowledge/reflect has been remarkable!‘

‘Importantly, we have also worked hard with the family to help them to accept him developing into a young adult with sexual feelings and the need to have access to peer relationships.‘

‘The Mat was brilliant in bringing all this together and providing the scaffolding to have these discussions with him.’

As a speech and language therapist, this process has been such a fantastic learning experience. It has been a joy and a privilege to work together with our social work and Talking Mats colleagues to create what will hopefully become an invaluable and essential resource in this field.

We are looking forward to sharing more information about the project and resource in an Advanced Webinar for practitioners who have already completed Talking Mats Foundation Training, in September 2024.

Inspired to think about Talking Mats Foundation Training? Find out about all the options we have available here.

This year’s campaign focuses on the importance of all children and young people whoever they are, and wherever they are in the world, to be able to say – and believe – “My Voice Matters.” Talking Mats is a tool that allows the voice of the young person to be heard. Read these blogs on Mental Health and Young People to find out more.

- Dr Carla Innes, Clinical Psychologist for Learning Disabilities at Stockport Healthy Young Minds (CAMHS) describes how Talking Mats helps the team to gain more insight to the children and young people they are working with, and how it has helped intervention focus on the child’s potential, and zone of proximal development.

- This work in Stockport is further expanded on in a presentation by Dr Rosie Noyce, Clinical Psychologist, given at the Talking Mats 21st Birthday Event in August 2019.

- Sally Kedge, SLT with Talking Trouble, New Zealand shares 2 powerful case examples of using Talking Mats with children and families caught up in the Criminal Justice System and demonstrates how the connection with a therapist can be the key to unlocking feelings and emotions

- Natalie Paris, Project Lead for Cashback180 programme based within Mayfield and Easthouses Youth 2000 Project, shares stories of using Talking Mats with young people in Midlothian.

- Our Director, Margo MacKay, describes using Talking Mats to ask young people about their environment and the impact different environments can have on wellbeing.

- Laura Holmes, our Lead Associate for Children and Young People, writes about the Virtual Schools Team in Wigan and how they used Talking Mats with Looked After Children.

To find out more about Talking Mats Foundation Training for you or your organisation, click here.

When this blog from Janie Scott, a Talking Mats Licenced Trainer with Perth and Kinross Council came in I was a bit stumped. There was a lot that I wanted to highlight but I didn’t want to focus on one thing and detract from others:

- The importance of understanding and applying the Talking Mats framework allowing conversations on topics not covered by our resources.

- Demonstrating how Talking Mats can enable the voice of the child to be heard, upholding Scotland’s Promise to care experienced children, young people, and families.

- A model for embedding Talking Mats in a service.

I decided to go with everything. In 2 parts.

Part 1

Talking Mats; UNCRC, the Promise and hearing the thinker:

Janie Scott, (Highly Specialist SLT Perth & Kinross Council)

Scotland is currently progressing with the incorporation of the United Nations Conventions on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) through the UNCRC (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill.1 The UNCRC, article 12, states that, ‘children have the right to give their opinions freely on issues that affect them. Adults should listen and take children seriously.’

Talking Mats enables rights-based participation for children, allowing them to form and express views freely. It allows others to understand the issues and, as stated above, have those views taken seriously 2

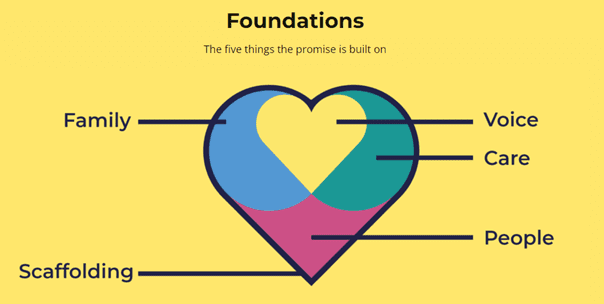

The ‘voice’ of the child is central to The Promise3. Talking mats should be considered the ‘scaffolding’ to enable a voice to be heard.

Last year I rolled out Talking Mats foundation training to Social Workers and Senior Social Care Officers working within Services for Children, Young People and Families, in Perth and Kinross Council. Fundamental to Talking Mats is the framework; the ability to use an appropriate top scale, open questions, silence and pass control to the thinker. Having demonstrated the importance of the framework in the training, we then went on to develop symbol sets specifically related to the work of the Social Work teams. These covered a wide range of topics including:

- sleep

- becoming a foster family

- contraception

- sexual knowledge

- contact arrangements,

- behaviours that adopted children think might be difficult to deal with

- grief

- school life

- triggers (related to drugs and alcohol)

I was privileged to hear several reports of how Talking Mats had allowed the voice of the children and young people to be heard which had a direct positive impact on their lives. Here are two powerful examples from a parent and a social worker.

Parent

” I have really enjoyed using Talking Mats. It lets me see everything in an organised way. I really like that. It has also shown me the progress I have made; I have found using an advocate really useful in the past but I don’t need to use an advocate any more as I feel more confident. I used to struggle with making decisions but this mat made me realise that I make decisions all the time and they are not wrong decisions.”

Assessing Social Worker for Kinship Care

“As part of my role, I need to find out information from teenagers on how they feel their kinship placement is going. Typically I find that many teenagers give one word answers or sometimes they tell me what they think I want to hear. Talking Mats has been useful in my work in allowing teenagers to open up. It has also been useful with children who have English as an additional language. The children did speak English, but it made it easier to get their ‘story’ from them.

“There was one particularly quiet and reserved teenage boy who was reluctant to share information. The Talking Mat allowed him to tell me much more than when I had initially questioned him. Through the Mats we were able to distinguish the difference he felt between living at home and living with his kinship carers. The Talking Mat enabled him to express that his kinship carers were open to having discussions with him and talking about his worries whereas his Mum did not want to talk about his worries. this was something that I was able to support him in sharing with his Mum as part of the plan for him to return home.“

To uphold Article 12 services must be proactive in creating opportunities to listen to the voice of the child. Talking Mats is enabling the voices of children, young people and families to be heard in Perth and Kinross. This voice is influencing key decisions in their lives across a variety of forums including the Children’s Hearing System, Kinship Panels, and Child’s Plan Meetings.

- Children’s rights legislation in Scotland: quick reference guide – gov.scot (www.gov.scot) ↩︎

- Can Scotland be Brave – Incorporating UNCRC Article 12 in practice – gov.scot (www.gov.scot) ↩︎

- Foundations of the promise – The Promise ↩︎

Talking Mats Director, Margo MacKay, will be presenting with Laura Lundy, Professor of International Children’s Rights, QU, Belfast on Wednesday 1st of November, 2023 at NHS Education Scotland webinar; ‘The voice of the infant and child; rights- based participation for children and young people’

For more details please see the NES website.

Read ‘Can Scotland Be Brave, Incorporating UNCRC Article 12 in practice here

Thank you to Lisa Chapman,Lead Speech and Language Therapist at Bee U: Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services, Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, who has shared her thoughts about the new sensory resource, sharing what it means to her both professionally and personally. Use these links to read more about the resource and our giveaway offer and to book directly.

A personal and professional journey intertwined.

Communication has always been one of my passions. As a languages teacher I was struck by the speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) of my students and this led me to retrain as a Speech and Language Therapist (SLT). As a parent I saw how my youngest son struggled to communicate his needs and how others struggled to understand him across different environments. He now has a diagnosis of Autism and the experiences we have had together were the start of my journey to explore Sensory Processing.

Sensory Processing, Sensory Integration and Neurodiversity.

Sensory processing is something we all do, it is how we make sense of the world around us using our 8 senses. These websites offer a good general overview of our senses and sensory processing;

- Understanding Sensory Processing and Integration in Children (sensoryintegrationeducation.com)

- Free online sensory processing course for teachers, assistants and parents (griffinot.com)

How this information is then dealt with is referred to as ‘Sensory Integration’; ‘the processing, integration and organisation of sensory information from the body and the environment’ (Schaaf & Mailloux, 2015, p5).

From my growing personal interest came ideas on how sensory processing and integration overlapped with my professional life as an SLT. Hooked, I enrolled on the Sensory Integration Masters course with Ulster and latterly Sheffield Hallam University. I completed my Diploma in 2021 and hope to complete my Masters dissertation later this year.

I love that I have been able to weave my ‘lived’ experiences into my professional development. These experiences continue to overlap. Most recently, this has involved exploring the concept of Neurodiversity, “the infinite variation in neurocognitive functioning within our species” (Walker, 2014a). Walker clarifies that the neurodiversity paradigm has three fundamental principles

• Neurodiversity is natural and valuable. We are stronger because of our diversity.

• There is no one ‘right’ way to process information. There is no such thing as a ‘normal’ brain.

• It is important to acknowledge social power dynamics exist in relationship to diversity. Walker (2014b) reminds us to ‘check’ our privilege. This will frequently involve moving out of our comfort zone (Murphy, 2022).

This paradigm has become a core framework for me as both an SLT and a parent. It helps me make sense of variations in communication and sensory experience, to reframe these as differences, not deficits. Understanding my son’s sensory processing has helped me see the world through his eyes allowing new spaces for communication and different conversations. It has helped to reduce the Double Empathy gap (Milton, 2012).

I am equally aware of the impact of environments. Luke Beardon’s (2017) ‘golden equation’, one I quote often, aptly summarises this. “Autism + Environment = Outcome”. Environment here includes identity, the sensory environment, other people and society (Beardon, 2022). The value of having a clearer understanding of your identity and needs is also context dependent, ‘relational’ (Chapman, 2021). You, and others around you, may have great insight into how your body and mind work, but this can only go so far. If no one is listening to you, and environments in their broadest terms are set up to be against you, are ‘low-functioning’ (Patten, 2022, p.8), it is harder to achieve positive and authentic outcomes.

For my autistic son, education settings have sadly often been ‘low-functioning’ environments, placing an immense toll on his sensory processing, communication and ultimately on his emotional well-being. The impact on us as parents has been no less challenging, coping with multiple exclusions from multiple placements. I have equally seen the power of restorative, ‘high-functioning’ environments (Patten, 2022, p.12) that enable him to be the best he can be: environments that offer success, building on his interests and abilities.

The very nature of neurodiversity suggests that we all process sensory information differently. A better understanding of individual sensory experiences gives more information that we can use to create and advocate for ‘high functioning’ environments for everyone, and achieve equity. A crucial first step in neurodiversity affirming practice is respecting an individual’s ‘epistemic authority’ (Chapman & Botha, 2022). To listen without prejudice, and not to enforce that we know best, just because of our position.

With this as my personal and professional ‘framework’ I welcomed the opportunity to trial the Talking Mats resource; Me and My Senses and my final thoughts are around using it with my son.

My personal journey continues; learning and growing

As his mum, and as an informed professional, I felt that I already knew my son’s sensory profile, that I could predict what some of his answers were going to be. He had also already had a full OT-ASI assessment. I came to this as an exercise in ironing out snags, not primarily one of personal learning. I couldn’t have been more surprised by the wealth of new information I came away with, after using the mat with him.

My most important learning was around the significance of smell for my son. Using the mat gave him the space and opportunity to share his insights into smell that I had never really appreciated before. What’s more, this ‘opening up’ extended beyond the time we were using the mat. For the rest of the day he continued to refer to his mat, adding further examples and anecdotes about ‘smell’ as a fundamental sense for his well-being. The mat had provided a safe space for exploration, connection and communication beyond its physical presence. It was a humbling, but also precious experience. It illustrated beyond doubt the importance of listening, but also the immense privilege of opening up and sharing a space that facilitated my son’s voice to be heard.

Until now, few tools have captured the lived ‘sensory’ experiences of children and young people. The Talking Mats ‘Me and My Senses Resource’ meets this need. It places an individual’s voice as central, acknowledging and facilitating autonomy and agency. As such, it is an invaluable tool to anyone wishing to explore sensory processing in a neurodiversity affirming way.

References

Beardon, L., (2017, July). How can unhappy autistic children be supported to become happy autistic adults? https://blogs.shu.ac.uk/autism/files/2017/07/How-can-unhappy-autistic-children-be-supported.pptx

Beardon, L. [@SheffieldLuke]. (2022, December 11). Autism + environment = outcome; environment could include: autistic self (e.g. understanding of self); others in that environment; the sensory. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/SheffieldLuke/status/1601894447721111552?s=20&t=HmyywdI4gDSrDJ1BggtF3w

Chapman, R. (2021). Neurodiversity and the Social Ecology of Mental Functions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1360–1372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620959833

Chapman, R., & Botha, M. (2022). Neurodivergence-informed therapy. Developmental Medicine Child Neurololgy. 00: 1– 8. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15384

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The “double empathy problem”. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883-887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

Murphy, K. (2022). Neurodiversity in the Early Years. Neurodiversity & ableism reflection tool. https://assets-global.website-files.com/5f903cbab2ae71f26cf02400/638a04bcc5a15c6fda2c02b1_AUDIT_Kerry%20Murphy.pdf

Patten, K. K. (2022). Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture—Finding our strengths: recognizing professional bias and interrogating systems. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76, 7606150010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2022.076603

Schaaf, R.C. & Mailloux, Z. (2015). Clinician’s guide for implementing Ayre’s sensory integration: Promoting participation for children with autism. American Occupational Therapy Association: Incorporated.

Walker, N. (2014a). Neuroqueer: The writings of Dr. Nick Walker. Neurodiversity: Some basic terms & definitions. https://neuroqueer.com/neurodiversity-terms-and-definitions/

Walker, N. (2014b). Neuroqueer: The writings of Dr. Nick Walker. Neurotypical psychotherapists & autistic clients. https://neuroqueer.com/neurotypical-psychotherapists-and-autistic-clients/

After many months of work the new Talking Mats sensory resource; Me and My Senses is reaching the final phase and registrations open on Friday 31st March for our launch seminar. This blog gives an overview of what’s in the resource and our guest blog to be published on Friday is a powerful story of professional and personal learning with ‘Me and my senses’ playing a pivotal role.

The resource will aim to enable children and young people who have speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) and sensory integration difficulties to have a voice in their therapy assessment, planning and intervention. To find out more about the funding and development for this project please read the earlier blog here. It is also aimed at supporting all practitioners, regardless of their level of sensory integration training, to gain an individual’s voice of their ‘lived’ sensory experiences, needs and challenges.

It is divided into the following topics:

- My Spaces & Things I Do

- My Senses 1: Proprioception & Interoception

- My Senses 2: Vestibular

- My Senses 3: Taste, Smell, Hearing, Seeing, Touch

Use of the resource may contribute to sensory integration evaluation but does not replace a full sensory integration assessment, however it may equally work as a stand alone-tool. We hope that professionals from healthcare,education, in both mainstream and specialist settings, as well as colleagues in social care will value this resource.

Talking Mats is hosting an online seminar to introduce the resource and we have 50 sets to give away for free to the first 50 people who register for the seminar and are already Talking Mats trained. Registrations open on Friday.

In the first of 2 blogs on Selective Mutism, Vanessa Lloyd of Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS FT describes using Talking Mats to give a young boy the opportunity to communicate at a time when talking was too hard.

Using Talking Mats with a primary school aged child with developmental Selective Mutism

Selective Mutism is a form of social anxiety characterised by stark differences in how a person communicates in different situations. There is also acute awareness of everyone around them who may be listening, either intentionally or accidentally. In Education settings Selective Mutism often become apparent at times of transition and teachers often describe a very different child to the one a parent knows at home. As a school therapist I have the job of finding the puzzle pieces and bringing them together in a way that home and school can understand. I have found the Talking Mats approach to be very useful when working in this area. Here’s an example;

I recently took a referral for ‘A’ who is 6 years old:

Main points from school:

- Joined 12months ago

- Not spoken at school in those 12 months

- Staff felt they didn’t know him

- Staff assumed he was happy not joining in

Main points from parents:

- Aware he is quiet in school

- This is who he is and he has been like this since starting Nursery

My observations indicated Selective Mutism;

- his body language indicated anxiety in situations where he was expected to speak or interact

I needed a way to feedback this anxiety to staff and for A to be heard without using his voice. After building a rapport with him I introduced Talking Mats and offered him the opportunity to engage

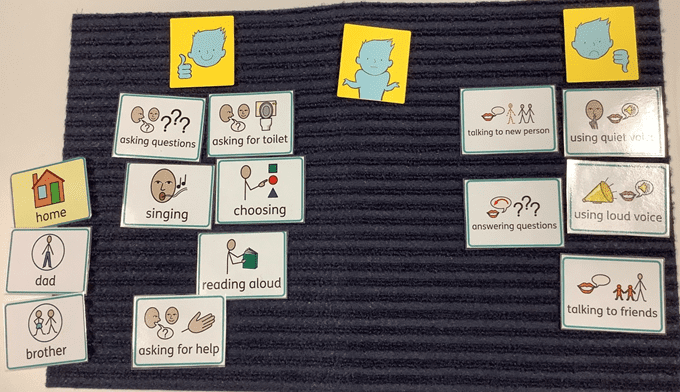

Getting Started

Using the Primary Communication Rating Scale (Johnson & Wintgens, 2016) as a basis, combined with an image system he was familiar with, I planned the symbols needed to support the conversation and set out the expectations for the activity. Fundamentally, I made it clear that he did not have to talk to me to participate.

How it went

The school environment.

As anticipated, he made his feelings instantly clear about the activities where he was required to talk, rapidly sorting them into ‘unsure’ or ‘don’t like’.

What was less expected was how relaxed his body language became, particularly when I suggested showing his class teacher. It was as though he knew that there was some power behind his arrangement of these symbols and he was ready to embrace it.

Follow up

Talking at home.

Having fully grasped the potential of the task, this young boy set to work answering my questions through careful consideration and placement of symbols. The same questions that would otherwise spiral him into a freeze or flee response were now being answered with a newfound command of the situation. He had things to say, things he wanted people to know, and in that moment, he had a way of doing this

Taking it forward:

Showing the child’s perspective provided a powerful way of highlighting to school the misguided assumptions that had been made about his feelings and attitudes towards talking. The Talking Mat conversations opened the discussion about the importance of Selective Mutism intervention and created a platform for the child to be involved and be heard. He was a valued contributor in an environment which was previously inaccessible for him.

Online training login

Online training login