Talking Mats; Me and My Senses: part 2

Thank you to Lisa Chapman,Lead Speech and Language Therapist at Bee U: Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services, Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, who has shared her thoughts about the new sensory resource, sharing what it means to her both professionally and personally. Use these links to read more about the resource and our giveaway offer and to book directly.

A personal and professional journey intertwined.

Communication has always been one of my passions. As a languages teacher I was struck by the speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) of my students and this led me to retrain as a Speech and Language Therapist (SLT). As a parent I saw how my youngest son struggled to communicate his needs and how others struggled to understand him across different environments. He now has a diagnosis of Autism and the experiences we have had together were the start of my journey to explore Sensory Processing.

Sensory Processing, Sensory Integration and Neurodiversity.

Sensory processing is something we all do, it is how we make sense of the world around us using our 8 senses. These websites offer a good general overview of our senses and sensory processing;

- Understanding Sensory Processing and Integration in Children (sensoryintegrationeducation.com)

- Free online sensory processing course for teachers, assistants and parents (griffinot.com)

How this information is then dealt with is referred to as ‘Sensory Integration’; ‘the processing, integration and organisation of sensory information from the body and the environment’ (Schaaf & Mailloux, 2015, p5).

From my growing personal interest came ideas on how sensory processing and integration overlapped with my professional life as an SLT. Hooked, I enrolled on the Sensory Integration Masters course with Ulster and latterly Sheffield Hallam University. I completed my Diploma in 2021 and hope to complete my Masters dissertation later this year.

I love that I have been able to weave my ‘lived’ experiences into my professional development. These experiences continue to overlap. Most recently, this has involved exploring the concept of Neurodiversity, “the infinite variation in neurocognitive functioning within our species” (Walker, 2014a). Walker clarifies that the neurodiversity paradigm has three fundamental principles

• Neurodiversity is natural and valuable. We are stronger because of our diversity.

• There is no one ‘right’ way to process information. There is no such thing as a ‘normal’ brain.

• It is important to acknowledge social power dynamics exist in relationship to diversity. Walker (2014b) reminds us to ‘check’ our privilege. This will frequently involve moving out of our comfort zone (Murphy, 2022).

This paradigm has become a core framework for me as both an SLT and a parent. It helps me make sense of variations in communication and sensory experience, to reframe these as differences, not deficits. Understanding my son’s sensory processing has helped me see the world through his eyes allowing new spaces for communication and different conversations. It has helped to reduce the Double Empathy gap (Milton, 2012).

I am equally aware of the impact of environments. Luke Beardon’s (2017) ‘golden equation’, one I quote often, aptly summarises this. “Autism + Environment = Outcome”. Environment here includes identity, the sensory environment, other people and society (Beardon, 2022). The value of having a clearer understanding of your identity and needs is also context dependent, ‘relational’ (Chapman, 2021). You, and others around you, may have great insight into how your body and mind work, but this can only go so far. If no one is listening to you, and environments in their broadest terms are set up to be against you, are ‘low-functioning’ (Patten, 2022, p.8), it is harder to achieve positive and authentic outcomes.

For my autistic son, education settings have sadly often been ‘low-functioning’ environments, placing an immense toll on his sensory processing, communication and ultimately on his emotional well-being. The impact on us as parents has been no less challenging, coping with multiple exclusions from multiple placements. I have equally seen the power of restorative, ‘high-functioning’ environments (Patten, 2022, p.12) that enable him to be the best he can be: environments that offer success, building on his interests and abilities.

The very nature of neurodiversity suggests that we all process sensory information differently. A better understanding of individual sensory experiences gives more information that we can use to create and advocate for ‘high functioning’ environments for everyone, and achieve equity. A crucial first step in neurodiversity affirming practice is respecting an individual’s ‘epistemic authority’ (Chapman & Botha, 2022). To listen without prejudice, and not to enforce that we know best, just because of our position.

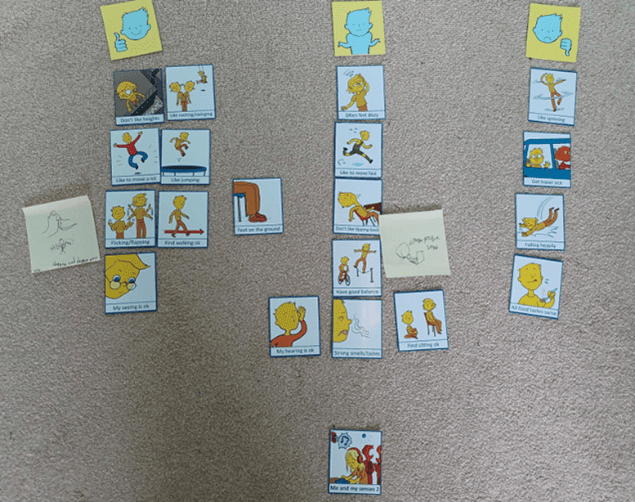

With this as my personal and professional ‘framework’ I welcomed the opportunity to trial the Talking Mats resource; Me and My Senses and my final thoughts are around using it with my son.

My personal journey continues; learning and growing

As his mum, and as an informed professional, I felt that I already knew my son’s sensory profile, that I could predict what some of his answers were going to be. He had also already had a full OT-ASI assessment. I came to this as an exercise in ironing out snags, not primarily one of personal learning. I couldn’t have been more surprised by the wealth of new information I came away with, after using the mat with him.

My most important learning was around the significance of smell for my son. Using the mat gave him the space and opportunity to share his insights into smell that I had never really appreciated before. What’s more, this ‘opening up’ extended beyond the time we were using the mat. For the rest of the day he continued to refer to his mat, adding further examples and anecdotes about ‘smell’ as a fundamental sense for his well-being. The mat had provided a safe space for exploration, connection and communication beyond its physical presence. It was a humbling, but also precious experience. It illustrated beyond doubt the importance of listening, but also the immense privilege of opening up and sharing a space that facilitated my son’s voice to be heard.

Until now, few tools have captured the lived ‘sensory’ experiences of children and young people. The Talking Mats ‘Me and My Senses Resource’ meets this need. It places an individual’s voice as central, acknowledging and facilitating autonomy and agency. As such, it is an invaluable tool to anyone wishing to explore sensory processing in a neurodiversity affirming way.

References

Beardon, L., (2017, July). How can unhappy autistic children be supported to become happy autistic adults? https://blogs.shu.ac.uk/autism/files/2017/07/How-can-unhappy-autistic-children-be-supported.pptx

Beardon, L. [@SheffieldLuke]. (2022, December 11). Autism + environment = outcome; environment could include: autistic self (e.g. understanding of self); others in that environment; the sensory. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/SheffieldLuke/status/1601894447721111552?s=20&t=HmyywdI4gDSrDJ1BggtF3w

Chapman, R. (2021). Neurodiversity and the Social Ecology of Mental Functions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1360–1372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620959833

Chapman, R., & Botha, M. (2022). Neurodivergence-informed therapy. Developmental Medicine Child Neurololgy. 00: 1– 8. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15384

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The “double empathy problem”. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883-887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

Murphy, K. (2022). Neurodiversity in the Early Years. Neurodiversity & ableism reflection tool. https://assets-global.website-files.com/5f903cbab2ae71f26cf02400/638a04bcc5a15c6fda2c02b1_AUDIT_Kerry%20Murphy.pdf

Patten, K. K. (2022). Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture—Finding our strengths: recognizing professional bias and interrogating systems. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76, 7606150010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2022.076603

Schaaf, R.C. & Mailloux, Z. (2015). Clinician’s guide for implementing Ayre’s sensory integration: Promoting participation for children with autism. American Occupational Therapy Association: Incorporated.

Walker, N. (2014a). Neuroqueer: The writings of Dr. Nick Walker. Neurodiversity: Some basic terms & definitions. https://neuroqueer.com/neurodiversity-terms-and-definitions/

Walker, N. (2014b). Neuroqueer: The writings of Dr. Nick Walker. Neurotypical psychotherapists & autistic clients. https://neuroqueer.com/neurotypical-psychotherapists-and-autistic-clients/

Online training login

Online training login